Skyscraper-scraping shelf cloud

Few things compare to capturing a shelf cloud invading the city. The otherworldly-ness of this cloud formation’s texture, shape, and moody light makes for truly unique scenes. Especially when it dwarfs Chicago’s skyline. And their rarity makes them especially satisfying to catch. People have asked me how I catch them, so I tried to answer that question in following post.

On June 30, 2019 I captured the lead-in photo from the 18th Street bridge over Ping Tom Park. Using my Nikon D800 & Nikkor 24-70 f/2.8, the image settings were; 36mm, ISO 320, f/8, 1/640. I used a tripod and a remote release for the sharpest possible photos. While shelf clouds look ominous, the structure itself is benign; though gusty winds and drenching rains usually trail closely behind.

Here’s the most basic description of what’s happening:

Rain cooled air spills out ahead of the storm, and wedges the warm air ahead up into the atmosphere. As that warm, humid air rises, it cools and condenses into droplets that shape the front edge of the cloud – not unlike when you can see your breath on a cold day.

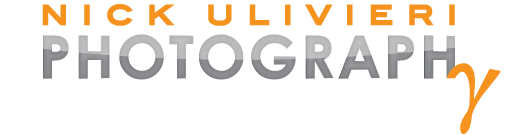

While your camera settings will vary based on local conditions, the hard part is getting into the right position. But predicting which storms will have a photogenic shelf cloud is tricky business. There’s no single thing on radar that’ll definitively render a shelf cloud’s outline, but some radar returns are more favorable than others. Here are a few screen grabs from my favorite radar app, Radarscope, that illustrate my point.

A linear, bowing storm (left), with a sharp color gradient is more far likely to produce a shelf than a scattered mix of storm cells (right). An outflow boundary (pink arrows, left frame), may also hint at a shelf cloud. However, a boundary doesn’t guarantee a shelf cloud will materialize. Long story short, get out ahead of a well-organized storm and cross your fingers.

But there’s another secret weapon I use; social media, specifically Twitter. Shelf clouds can travel long distances and Wx-minded photographers are likely sharing photos while it’s still hundreds miles away. And if you follow enough meteorologists on Twitter, there’s a good chance you’ll see a photo of it before it arrives in your area.

Basically, Twitter sometimes confirms my radar-induced hunch, and once that happens, I venture out and…wait. I like to pick a location where I can photograph the storm approaching from behind the skyline for maximum “shelf” effect. If you’re positioned in such a way that the self cloud rolls over you from behind, you’ll most likely miss out on the cloud’s layered structure. In other words, pick a composition that allows you to point your camera at the approaching system.

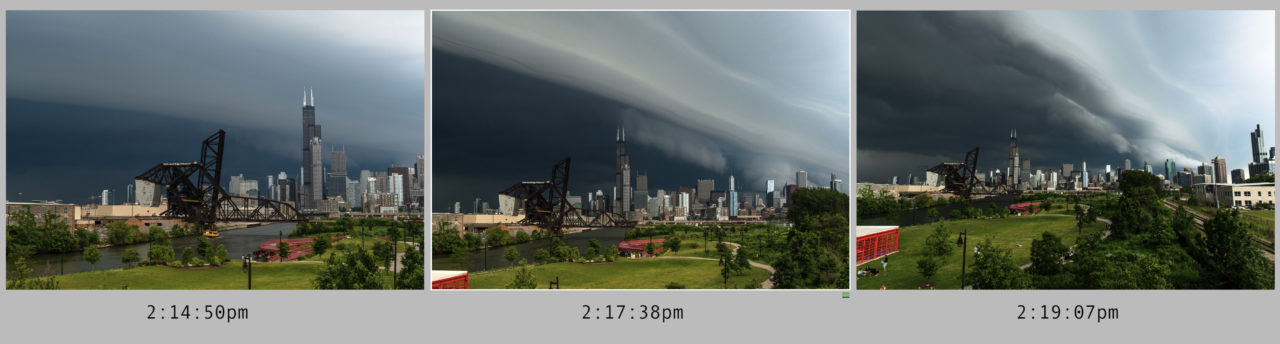

Shelf clouds also roll in fast! While it may take a good half hour for the sky to darken and the shelf to become visible, peak ‘shelfage’ may only last a few fleeting minutes. Here’s another comparison with timestamps. The feature photo is in the center. In the first frame, the shelf still isn’t close enough to discern its texture or appreciate its size. And in the third photo, the leading edge of the storm has almost eclipsed my position. To me, the middle photo is just right – it’s in the goldilocks zone, so to speak.

While every shelf cloud is unique, and moves at different speeds, you can see just how fast things change. You’re best bet is to get out there before the storm arrives and hope Mother Nature puts on a show.

Just a couple days before, I caught another shelf cloud from 360 Chicago. If you want to see some of those shots, check out my recent Facebook post.

Happy storm chasing…or waiting!

P.S. Props to Andrew Pritchard // @SkyDrama for answering many of my shelf cloud related questions. And if you want another explanation of how shelf clouds form, check out the first few minutes of Andrew’s recent forecast.